Origins

The International University Campus in Paris (CIUP) is an architectural complex known for the character and variety of its buildings, which reflect the talent and cultural diversity of their builders. Set in 34 hectares of landscaped park, the 37 residences and communal buildings form a real showcase of twentieth century architecture. Standing on this campus is the Swiss Pavilion, an architectural gem listed as a historical monument in December 1986.

It was in 1924 that Switzerland decided to build a pavilion on the CIUP. From 1925 to 1930, a committee worked to raise private funds and secure a Swiss Federal Government grant. At the behest of Professor Rudolf Fueter, mathematician and Rector of the University of Zurich, it was decided to commission Le Corbusier to build the pavilion. The architect, still smarting from his failure at the 1927 competition for the League of Nations Palace, was initially hesitant. He finally accepted, persuaded that “in Paris, it was important that Switzerland appear in another guise than the poet’s rustic image of chalets and cows”.

After seemingly interminable negotiations, the foundation stone was finally laid on 14 November 1931. The building was inaugurated in July 1933, and stood out as the only construction on the CIUP with an explicitly modern identity, far removed from any folk style or academic tradition – a modern image that Switzerland consistently sought to portray at international events at that time. Its creators, Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret, made the Swiss Pavilion the testing ground for their vision of collective housing and their theories of contemporary construction: strength of the lower structure in reinforced concrete, industrial prefabrication of the floors, carefully researched sound insulation and a highly functional room layout planned in collaboration with interior designer Charlotte Perriand.

The Design

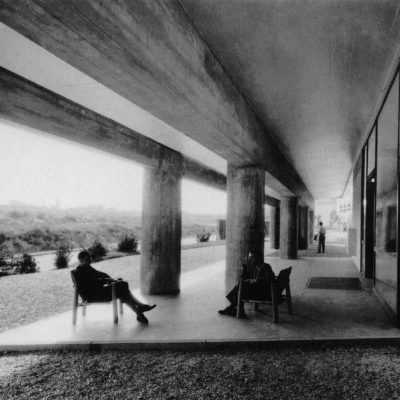

Between December 1930 and July 1931, four designs for the Swiss Pavilion were presented. Doubtless because of the client’s concern to limit costs, the architectural brief was kept to a strict minimum: forty-two rooms for students, a lounge area, an entrance hall, an office and an apartment for the director. The architect’s proposals managed to expand this programme a little, particularly by adding ample circulation space. In spite of the limited dimensions (2.8 x 6m), the strength of the design lies in the room layout, furniture and natural light from the south-facing horizontal windows. The rooms are all basically identical, and for many years were the only ones at the CIUP equipped with a shower. The spatial combinations and architectural expression were very new; they were inspired by the latest concepts and to some extent by the “five points of a new architecture” defined by Le Corbusier and Jeanneret in 1927. Given the difficult ground conditions (the site was formerly a quarry), the architects opted to limit the number of piles (19m deep) for the foundation and to feature this technical aspect by elevating the main building above ground level, on what they called an “artificial ground” supported by the exposed pile foundation. Pleased by their collaboration with the industrialist Wanner (“Clarté” apartment building in Geneva, 1930-1932), the architects first envisaged a steel structure before deciding on a more complex structural system. Above the massive pillars in reinforced concrete, the floors were built with a lightweight steel frame, clad in brick, artificial stone and abundant glazing.

A “house of modern culture”

Recognised as “one of Le Corbusier’s freest and most imaginative creations” (Sigfried Giedion), the building combines three approaches: one embraces the modern apartment-block style, independent of any relation to the shape of the plot; the second confronts this block with different, specialized volumes, combines flat and concave walls, and contrasts industrial and natural materials. The third is in the original interpretation of two of the “five points of modern architecture”: the accessible yet hidden roof garden and the pillars in exposed concrete. As such, the building can be seen as the starting point for Le Corbusier’s further development as an artist and for the “new brutalism” of the 1950s.

The five points of architecture

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret developed a manifesto for contemporary architecture based on five principles – pillars, the roof garden, free design of the ground plan, the horizontal window, free design of the façade – of which the Swiss Pavilion provides a brilliant illustration.

The pillars

The house is in the air, away from the damp, dark ground; the garden moves under the house.

The roof garden

With the installation of central heating, the roof should be inward-sloping rather than humped. It should allow water to run towards the middle of the building, ensuring constant moisture on the roof that will enable an opulent roof garden to be created. At the Fondation suisse, the roof garden is hidden and inhabited.

The horizontal window

Reinforced concrete revolutionised the history of the window. With no need for supporting walls, windows can run from one side of the façade to the other.

Free design of the façade

The posts are set back from the façade, under the house, and the floor is cantilevered. The façades are no more than a light sheath of insulating walls or windows.

Free design of the ground plan

The ground plan is no longer defined by load-bearing walls. The reinforced concrete in the house allows for a free design. The interior layout of the floors is unrestricted.

Renovations

Le Corbusier returned several times for additional work on the Swiss Pavilion.

- 1948: a mural was painted to replace the photographic mural of 1933, which had been destroyed during the war.

- 1953: the southern wall was rebuilt, significantly transforming the floor to ceiling room windows to reduce excessive sunlight;

- 1957: a series of enamelled benches and new polychromy were added to the rooms.

The Swiss Pavilion was added to the supplementary historical monuments list in September 1965, then confirmed and classified as a historical monument in December 1986. The latest structural work was done in 1991-93, led by Hervé Baptiste, chief architect of historical monuments, and Jacques Chopinet, architect of the Fondation suisse. It involved repairing and waterproofing the roof terrace, and replacing all the artificial stone cladding. The cost of 4.5 million francs was evenly shared between the Swiss government and the French ministry of culture. More recently, electrical installations were updated, kitchenettes installed on each floor and the rooms refitted with new plumbing and appliances. New furniture was approved by Charlotte Perriand. One room is maintained as a prototype of the original and is open to visitors. In July 2000, Le Corbusier’s painted mural was restored by Madeleine Hanaire with funding from the Council of the Swiss Pavilion and the Regional Office of Historic Monuments. The Nevada glass tile wall was fully renovated in 2007. Finally, in 2016, the waterproofing of the roof terrace was re-established, and in 2018, under the direction of Alexandre Kabok, architect of the Fondation suisse, private bathrooms were integrated into the student rooms and the shared kitchens enlarged.